Permaculture

Summary

At its root, permaculture means taking natural ecosystems as the model for our own human habitats.

“Natural ecosystems are, almost by definition, sustainable, and if we can understand the way they work we can use that understanding to make our own lives more sustainable.” - Whitefield in The Earth Care Manual: A Permaculture Handbook for Britain & Other Temperate Climates

Central Ideas and Claims

“Perhaps we seek the Garden of Eden, and why not? We believe that a low-energy, high-yielding agriculture is a possible aim for the whole world, and that it needs only human energy and intellect to achieve this.”

– Mollison and Holmgren, Permaculture One.

The term “permaculture” was coined in 1978 by Bill Mollison and David Holmgren to describe an “integrated, evolving system of perennial or self-perpetuating plant and animal species useful to man”.B. Mollison & D. Holmgren, Permaculture One, Corgi 1978.

Holmgren has since defined permaculture as “consciously designed landscapes which mimic the patterns and relationships found in nature, while yielding an abundance of food, fiberfibre and energy provision for local needs”. Holmgren, D. Essence of Permaculture. Holmgren Design Services. 2007. p1. In application, permaculture can be understood more specifically as the use of systems thinking and design principles that provide the organizing framework for implementing this vision. With this understanding, permaculture as a design system can be applied to much else besides food growing, including buildings, settlement design and community development.

At the root of permaculture are certain fundamental assumptions about the world. Among these assumptions are: the tapping of fossil fuels during the industrial era is the primary cause of the explosion of the human population and of technology; the environmental crisis is real and threatens the wellbeing and survival of the world’s expanding population; global industrial society has resulted in massive changes to the world’s biodiversity in the last few hundred years, yet the future impacts of this growth on biodiversity is forecasted to be far greater than that already seen; the depletion of fossil fuels within a few generations will see a gradual return of system design principles observable in nature and pre-industrial societies, which are dependent on renewable energy and resources.

From the study of the natural world and pre-industrial sustainable societies, Holmgren and Mollison have derived “permaculture principles” – principles which are universally applicable to fast-track the development of sustainable use of land and resources. These principles can be divided into “ethical principles” and “design principles”.

Ethical Principles

Holmgren and Mollison outline three broad ethical maxims: care for the earth (husband soil, forests and water); care for people (look after self, kin and community; and fair share (set limits to consumption and reproduction, and redistribute surplus). These principles were arrived at through research into community ethics, as adopted by older religious cultures and modern cooperative groups, and now form the ethical foundations of the permaculture movement.

Design Principles

The scientific foundation for permaculture design principles is rooted predominantly in the modern science of ecology, and more specifically within the branch of “systems ecology”.

Permaculture uses design processes based on whole-systems thinking. In the Essence of Permaculture, Holmgren explains that a cultural bias towards focus on the complexity of details results in the complexity of relationships being overlooked:

"We tend to opt for segregation of elements as a default design strategy for reducing relationship complexity. These solutions arise partly from our reductionist scientific method that separates elements to study them in isolation. Any consideration of how they work as an integrated system is based on their nature in isolation."

Holmgren, D. Essence of Permaculture. Holmgren Design Services. 2007. p22.

Permaculture, on the other hand, focuses on the internal workings of ecosystems and holds that the connections between things are just as important as the things themselves. Holmgren explains that through careful consideration to the placement of plants, animals, earthworks and other infrastructures it is possible to develop a higher degree of integration and self-regulation without the need for constant human input in corrective management.

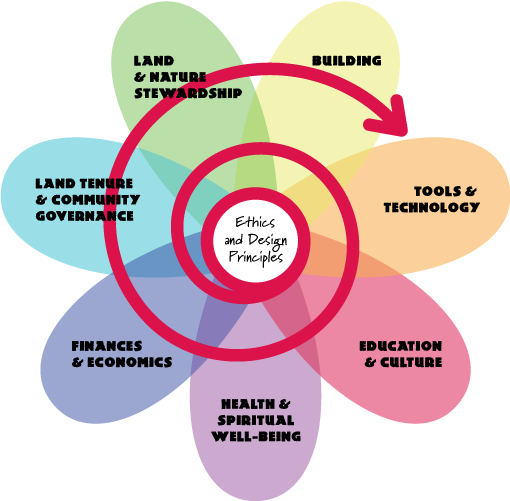

These ethics and design principles of permaculture, historically focussed on land and nature stewardship, are now being applied to other domains dealing with physical and energetic resources, as well as human organization. The Permaculture Design Flower, created by Holgren, displays the key areas to which permaculture ethics and design principles can be applied in order to achieve the required transformations needed for a sustainable future.

The Permaculture Flower. Credit: Permacultureprinciples.com

History

In the late 1960s, Bill Mollison, senior lecturer in Environmental Psychology at the University of Tasmania, and David Holmgren, graduate student at the Tasmanian College of Advanced Education, began developing ideas about stable agricultural systems on the Australian island of Tasmania. The term “permaculture” was then coined by the pair in 1978 in their book, Permaculture One.

Outlining the origins of the term in the Introduction to Permaculture, Bill Mollison and Reny Slay explain: “The word itself is a contraction not only of permanent agriculture but also of permanent culture, as cultures cannot survive for long without a sustainable agricultural base and landuse ethic.”Mollison, B. C. & Slay, R. M. Introduction to permaculture. Tyalgum, Australia: Tagari Publications, 1991.

Something akin to permaculture has been practiced for thousands of years across the world. For example, Indigenous inhabitants of both northern Tanzania and the Kandy area of Sri Lanka cultivate gardens which are modified versions of the natural forest vegetation. These gardens produce high yields while requiring no heavy energy input and resulting in no soil erosion.Whitefield, P. The Earth Care Manual: A Permaculture Handbook for Britain & Other Temperate Climates. New edition. Hampshire: Permanent Publications, 2011.

Central to Holmgren’s and Mollison’s formulation of permaculture was their recognition of the unsustainable nature of Western industrialized methods and their appreciation of Indigenous worldviews and practices. In the Essence of Permaculture, Holmgren states that:

"Focus in permaculture on learning from indigenous cultures stems from these cultures having existed in relative balance with their environment and surviving for longer than any of our more recent experiments in civilisation."

Holmgren, D. Essence of Permaculture. Holmgren Design Services. 2007. p8.

Permaculture has become a worldwide approach to land management, as well as a philosophy and movement. A network of individuals and groups has formed, spreading permaculture design solutions around the world.

Today, institutes of permaculture exist around the globe, including the Asian Institute of Sustainable Architecture in Hong Kong, The Mesoamerican Permaculture Institute in Guatemala and the Permaculture Institute of El Salvador.

Key Actors

- Bill Mollison

- David Holmgren

Key Texts

- Mollison, B. & Holmgren, D. Permaculture One. Corgi, 1978.

References

- Holmgren, D. Essence of Permaculture. Holmgren Design Services. 2007.

- Mollison, B. C. & Slay, R. M. Introduction to permaculture. Tyalgum, Australia: Tagari Publications, 1991.

- Whitefield, P. The Earth Care Manual: A Permaculture Handbook for Britain & Other Temperate Climates. New edition. Hampshire: Permanent Publications, 2011.

Further Reading

- Holmgren, D. Permaculture Principles & Pathways Beyond Sustainability. Holmgren Design Services, 2011.

- Mollison, B. C. Permaculture: A Designer's Manual. AU: Tagari Press, 1988.